Nature: An Exhibition by Ray and Millie Abell

Ray Abell

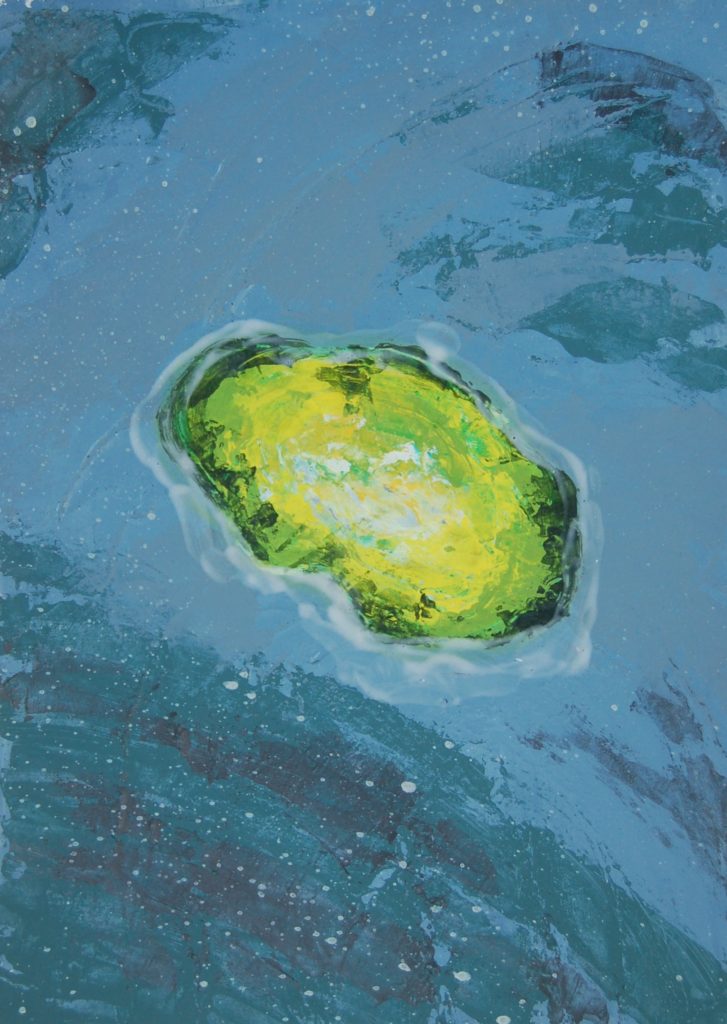

The idea for many of my nature paintings began at Shenandoah National Park while hiking with my wife Millie. We go to the park during all four seasons and my work draws from objects, patterns, and colors we find on those hikes, such as decaying trees, dried-out cicadas, moss-covered rock, fresh and stagnant water, and lightning-struck tree bark.

I spent three years in Saudi Arabia, and so the desert also has a special attraction to me; even now I look at sketches and photographs and paint from them. Some of the things that motivate me include: red and white sands; smooth and sharp rocks; mountain ranges; stillness; solitude; hot winds; the feel of dry desert heat; the smell of desert dust; the scent of dry and wet rocks.

I try to paint the feeling of walking through nature. I want to trigger the smells of grass, trees and rocks when dry and when wet. I want to capture the play of sunlight on soil, water and air. This is part of the essence of nature to me, and closeness to nature is important. I like to “push” my paintings from what I see to what I feel – that’s why I do abstractions.

I have a BFA in Painting from the University of Hartford, Hartford Art School, an MFA in Photography from Ohio University, and I completed the George Eastman House Advanced Studies Workshop in Rochester, NY.

Millie Abell

On our nature walks, I’m often drawn to seeds and shells, not just because they’re beautiful in their own right, but because of what they symbolize – seeds represent possibility, while shells indicate what became of possibility.

Words used to describe shells sound magical -- whorled; lustrous; luminescent; vaulted; chambered; sculpted; coiled; flared; beaded, etc. Helen Scales described the reason for their richly colored, complex patterns as nature having been “allowed to play.” Some compare their shapes and patterns to tree rings that record the life of a mollusk; for example, certain shells even generate a new layer of material with each tide. Collectors categorize the condition of shells on a scale ranging from “gem” to “poor” – ones that are faded, broken, with a “loss of character.” When walking the beach, I collect the latter, not just because there are more of them, but because they have the dicey past. The condition of a shell can tell us if its mollusk burrowed in the sand, thrived in rough waters, was attacked by predators, or was infested by other organisms.

I gather and wash flawed shells, then oil and varnish them to restore their color. For this exhibition, I arranged them so that their broken, irregular shapes form a larger whole. A Re-Membering depicts a headdress from a collective of imperfect shells, and although damaged, each is nevertheless, as Sandved and Abbott describe, “a story of growth and grace.”

Seeds symbolize possibility, and in collages I like to combine them with other symbols. For example, the moon often represents a pull on people, like it has on the tides. A scrap of map designates place, a shard of newspaper represents an everyday scenario in which we find ourselves; a fragment of watch indicates time, while string suggests connection. In The Ties That Bind, seeds glued onto newspaper and map denote our potential to use free will in a situation, while string connects our actions to decisions and actions of others in different circumstances and places.

I have a BS, MS, and PhD in the area of learning and instruction from Indiana University, where graduate coursework included the study of visual literacy and photography.