Geometrics

Juror: Reni Gower || Catalog || Flier

Awards:

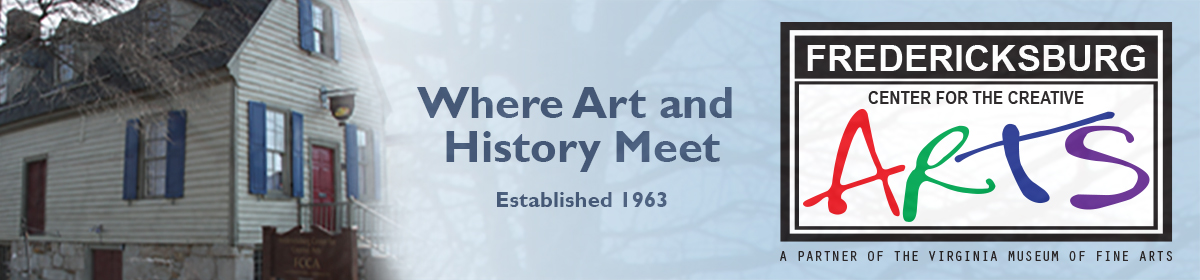

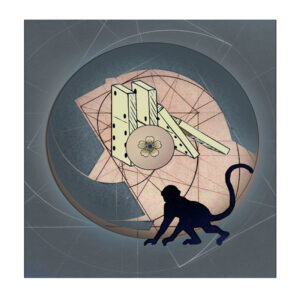

- 1st Place – “Crossing Over” original digital print by Robert Hunter of Colonial Beach, VA

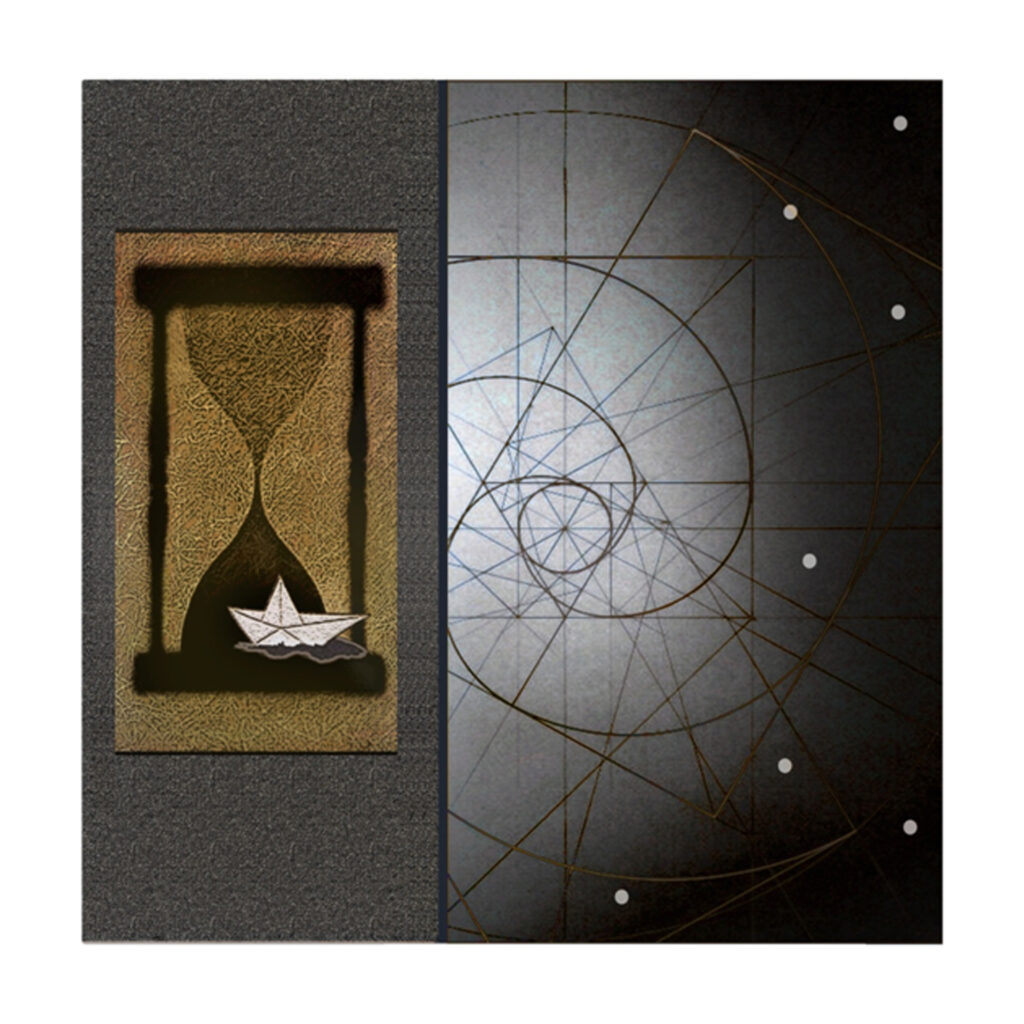

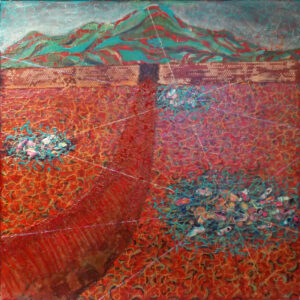

- 2nd Place –“Gypsy Portals #3” oil/cold wax painting by Bob Worthy of Montross, VA

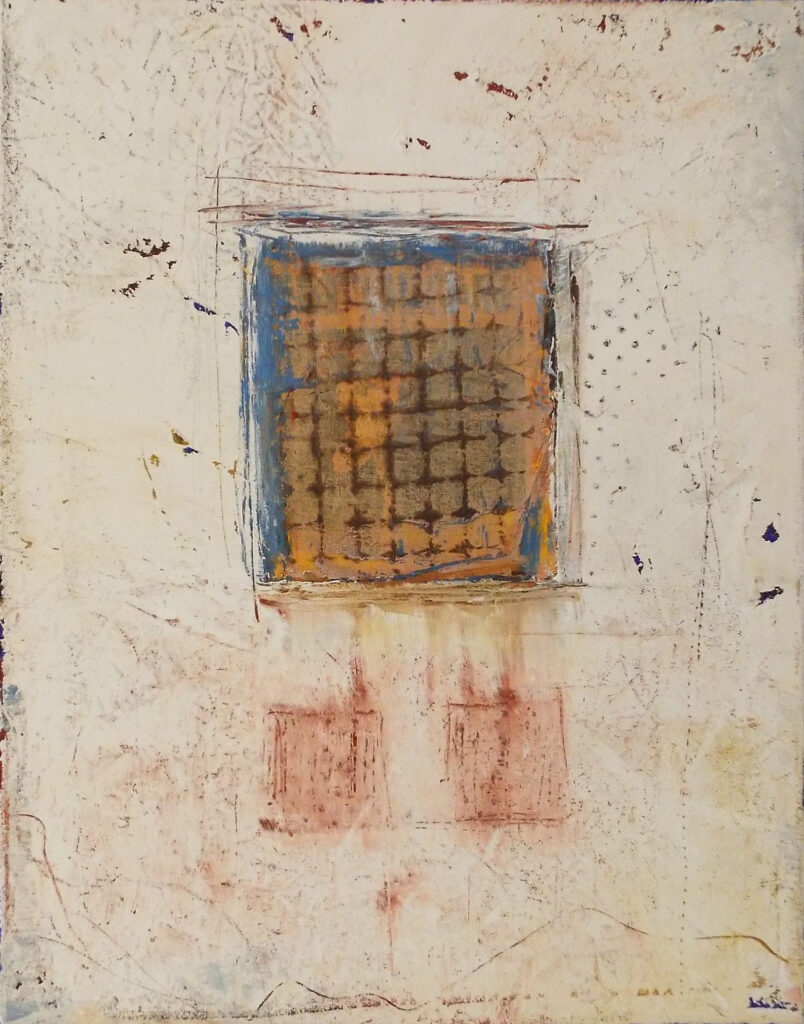

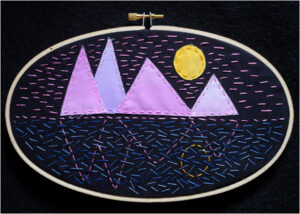

- 3rd Place – “High Speed” fiber art by Maura Harrison of Fredericksburg, VA

Honorable Mentions:

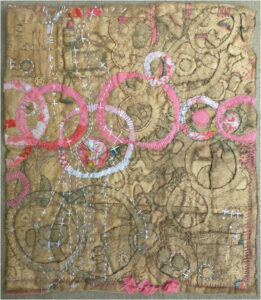

- “Chemical Attraction” mixed media by Michael Broadway of Woodford, VA

- “Falmouth Franks” oil painting by Marcia Chaves of Falmouth, VA

- “Stairway” photograph by Matt DeZee of Spotsylvania, VA

- “Eternity” mixed media painting by Sara Gondwe of Charlottesville, VA

Juror’s Statement:

Geometric perfection, also known as Sacred Geometry, is the matrix of humanity and the blueprint of the cosmos. Since ancient times, perfect forms (circle, square, and triangle) have been thought to convey sacred and universal truths by reflecting the fractal interconnections of the natural world. One finds these similarities embedded in decorative patterns of diverse cultures all around the globe. For instance, Islamic artists appropriated key elements from the classical traditions of Ancient Greece, Rome, and Persia to create a new decorative style based upon geometry. Likewise through ongoing migrations, comparable interlaced motifs and meanings are also found in Celtic knot work designs as well as Amish piece quilts. Our subconscious recognition of this collective symbolism is strikingly apparent on both micro and macro levels.

Using only a geometer’s tools (Compass, straight edge, pencil) it is easy to see how the circle is the source of all subsequent shapes and is often seen as the womb out of which all geometric patterns develop. Expanding from a single point to its perimeter, the circle implies the mysterious generation from nothing to everything and the finite to the infinite. To ancient mathematicians, the circle also symbolized the number one. Similarly, the number one creates all subsequent numbers. Thus the circle becomes a transcendental statement of the universe. The Flower of Life symbol (composed of 12 evenly-spaced overlapping circles) can be found in all major religions, as it contains all the patterns of creation as they emerged from the "Great Void” or divine source. With the internal ratios identical to cellular division, this structure also signifies all energy systems, including the human body.

The Fibonacci sequence or golden spiral also supports relationships between the circle and the five Platonic Solids, which Plato connected to the elements of fire, earth, air, water, and heaven. As such, they act as templates from which all life spring. Representing the purest expression of moving energy, the spiral’s role in nature is transformational. Consequently in myth and religion, the spiral signifies the path of spiritual and mystical transformation as well. Recognized since prehistoric times, nature’s golden spiral grows from within itself and increases according to the Fibonacci sequence. This perfect ratio can be seen in the growth spirals of pinecones, flower petals, and the branching patterns of trees. Contemporary science is now verifying on a sub-atomic level what the ancients knew all along, that the underlying geometric structure of the universe is visible.

Whether from the perspective of science, belief, or art; it is not hard to discover perfect harmony in the artworks I selected for Geometrics…

Look around the gallery: The Flower of Life is clearly evident in Tarver Harris’ Boundary Lines, a patterned work created with hexagons inscribed with overlapping circles. Likewise, the golden spiral is a powerful formal and symbolic structure in Penny Parrish’s vertigo inducing spiral staircase seen from above or in Robert Hunter’s prints that explore evolution, time, and infinity.

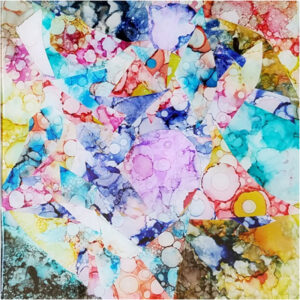

Mining the connectivity of cellular division, Michael Broadway’s Chemical Reaction, Maura Harrison’s fiber works, Van Anderson’s Kaleidoscope, and Sara Gondwe’s Eternity, all layer the circle in dynamic, but tangled organic systems.

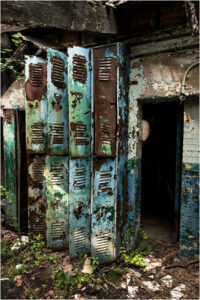

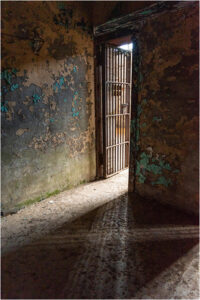

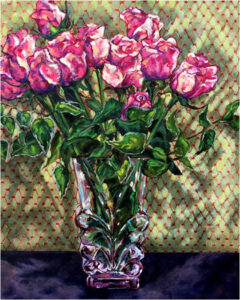

Squares figure prominently in many of the compositions as well. In The Red and The Black, Barbara Taylor Hall anchors her dramatic gestural abstraction with layered blocks of various sizes. Bob Worthy’s squares mysteriously emerge or dissolve in a soft wax scraffito haze. With a nod to Rothko, Kaye Lane’s floating and feathered squares are nonetheless compressed and solid. In contrast, Maria Motz scrubs her blocks and buildings with translucent colors and bold gestures. Katherine Owens stacks patterned and textured geometric shapes in satisfying arrangements of form and color. Whereas, Rebecca Carpenter’s photographs capture raw remnants inscribed into the derelict patterns of abandoned spaces. Likewise, a loose grid creates a luminous atmosphere in Teresa Blatt’s mysterious nocturnal landscape or Sallie Grant’s glimmering still life.

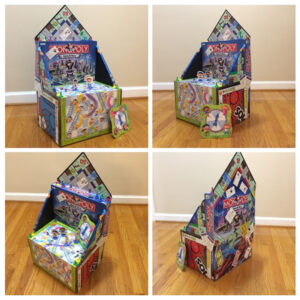

The triangle is also revealed as an integral structure in many of the artworks; such as Maria Chaves’ sundrenched small town market, the rocky shoreline of Bro Halff’s ocean view, Mary E. Johnson-Mason’s intimate landscapes collaged in cloth and drawn with thread, or the playful sculptural reinterpretation of Monopoly game boards in Elizabeth Shumates’ Game of Thrones.

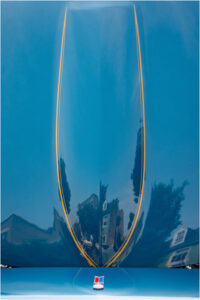

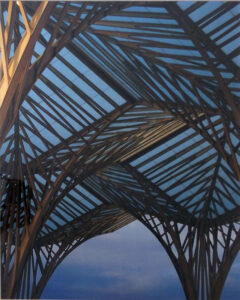

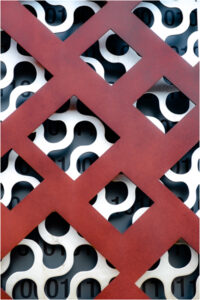

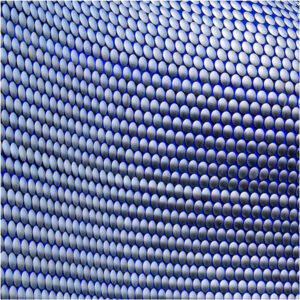

Many of the photographs, are transformative abstractions achieved by looking at recognizable objects up close. By looking through a micro lens, mesmerizing geometric patterns emerge in Addison Likins’ moiré patterns and glass membranes; Deborah Herndon’s flowing I-beam canopy or tetra stacked architecture; Mary Branscome’s optical ellipses; Carolyn Beever’s luminous street views; Matthew DeZee’s binary patterns or Escheresque staircase; Lee Cochrane’s organic gears; or Dorothy Stout’s iconic close-ups.

In contrast, several artists depict geometrics as a means of measurement. Though stark in black and white, Karie Anderson’s photograph reveals the highly calculated forms of carved and stacked stone. Whereas Patricia Smith speaks to the woven interconnectedness of all things by scribing a linear network over a vibrant landscape. Lastly, R. Taylor Cullar expertly crafts a meticulously ordered illusion that combines fantasy and fiction.

As artists, we are often drawn to geometry to create harmony and balance in our compositions. This is true for me as well. For my papercuts, prints, and paintings, I create new geometric iterations based upon the traditional patterns embedded in Islamic tile, woven Celtic Knots or Amish piece quilts. I believe by adapting or incorporating these forms and designs into our art, we can promote understanding and likewise encourage conversations between cultures different from our own. For me, art that speaks to a collective legacy between the West and the Middle East and beyond is a hopeful sign for our troubled times. It was my pleasure to jury Geometrics and I thank you for the opportunity to experience your work.